We know there’s a large gap between what people say and what they do. Since people make most of their decisions unconsciously, they’re often unaware of their everyday choices. This can make it hard to express needs or desires (if you think people know what they need: watch this (Dutch) video from 1999 in which people are asked whether they think they need a mobile phone).

When evaluating the user experience of existing products or services, this means we focus on observing behavior rather than listen to what participants have to say. But for designers who want to involve users in the early stages of a design process, the discrepancy between what people say and do can cause problems. How do you find out what your customers really need or want? What problems do they currently have? And what solutions would help them? Since asking them won’t work, we’ll need a different approach to find the answers to these questions.

Mapping your user’s context

Context mapping is a method for designing solutions that fit people’s everyday lives. This approach, developed at the Delft University of Technology, focuses on learning about needs, wishes, motivations and experiences. It’s a way to gather insights into the daily use of products and services in the context of the user. It can be applied to design new solutions or to improve existing products or services.

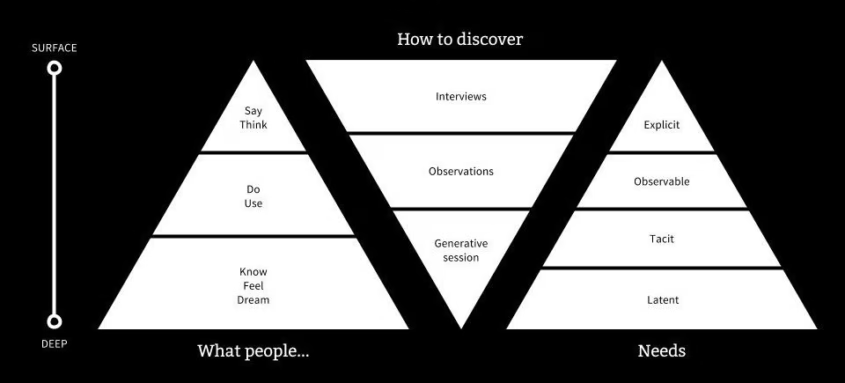

The approach combines different types of research methods. The visual below shows a number of these methods and the ways they can be used to acces different levels of knowledge:

Generative sessions

Recently, we worked together with the University of Applied Sciences Utrecht. The organization planned to redesign their (mobile) website, and we helped them to start this project by collecting relevant user insights.

We wanted to know what factors play a role in the process of choosing an educational programme. What goes on in these people’s lives at the moment they have to make this choice? How do they decide which university fits them best? Which persons and what events influence these decisions? Questions like these needed to be answered in order to find out in what way the university’s website could eventually play a role in this process.

To find these answers we conducted a generative session, a powerful context mapping technique. We invited a number of members from the target group: people who are planning to participate in an educational programme in the near future. By providing the participants with a set of hands-on exercises, we could map all kinds of latent needs and desires. These insights would later serve as the foundation of the redesign.

The timeline exercise

At first participants were asked to plot all of the important moments related to choosing an educational program on a timeline. What were important steps or decisions? What aspects played a role in this process? The participants all mapped their own personal journey, from the orientational phase to the moment they had actually signed up for a programme.

To help the participants on their way we provided them with stickers, icons and keywords that they could stick to their timeline. Some of these were just random pictures or words, others were derived out of our own primary assumptions. The participants could use this material in whatever way they wanted in order to express themselves.

The exercise forced the participants into associative thinking and helped them to recall relevant memories. This paved the way for the second part of session, in which they were asked to explain their creations to the group and the moderator. In another room, the university’s project team carefully monitored the session via a live stream.

The browser exercise

In the next exercise the participants were asked to create their own university website on a blank sheet of paper. They could write, draw or use some readymade components to make their own ideal web page. What type of information would they expect or hope to see first?

This assignment was mainly about prioritization, not about the way the website would actually have to be designed. Afterwards the participants were again asked to tell the rest of the group about what they had created.

Get to know your target group

A generative session is not about what timeline the participants make or about what type of websites they create. It’s about the experiences participants share during the explanation part, providing you with valuable insights into their personal lives.

This data serves as great input for customer journey maps, design guidelines and user stories. The things you learn about your customers will even go beyond the scope of using digital products. Getting to known them can uncover new ideas and business opportunities for your organization.

Why apply this approach?

By understanding context you can gather desires and needs that are relevant to your product, which you wouldn’t have found by simply asking your customers. It provides you with input for all kinds of deliverables and can help you steer the design and development of your website in the right direction.

Having your participants conduct a set of exercises, instead of just asking them a number of questions, has a lot of advantages. It puts the participants in the driver’s seat, enabling them to steer the conversation into the area of their expertise: their own experiences.

People are motivated by autonomy. By having them explain their own creations and talk about their point of view they are more likely to open up and share experiences and emotions. Actively doing things in a group bonds people together, increasing the level of involvement. Also, making something is just way more fun than being interviewed.

Combining qualitative and quantitative data

Beware, the input you gather from a generative session doesn’t tell you anything about quantity or importance of the issues, needs or desires or problems you encounter. It might therefore be a good idea to combine it with a quantitative approach, like an online survey in which you quantify and prioritize the needs you found. This way, you’ll be able to solidify the insights that you derived out of the generative session.